Historians Jared Frederick, host of Reel History, and Rich Condon analyze the strengths and weaknesses of the movie Free State of Jones. One of its greatest strengths, they agree, is the portrayal of post-Civil War “national reconciliation” as a tragedy that enabled pro-Confederates to destroy Mississippi’s fragile class and race-based era of Reconstruction and return pro-Confederate politicians to power. Institutionalization of White Supremacy followed.

A chilling story of murder from historian/songwriter Gregg Andrews

The Free State of Jones: A Review by “Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Two”

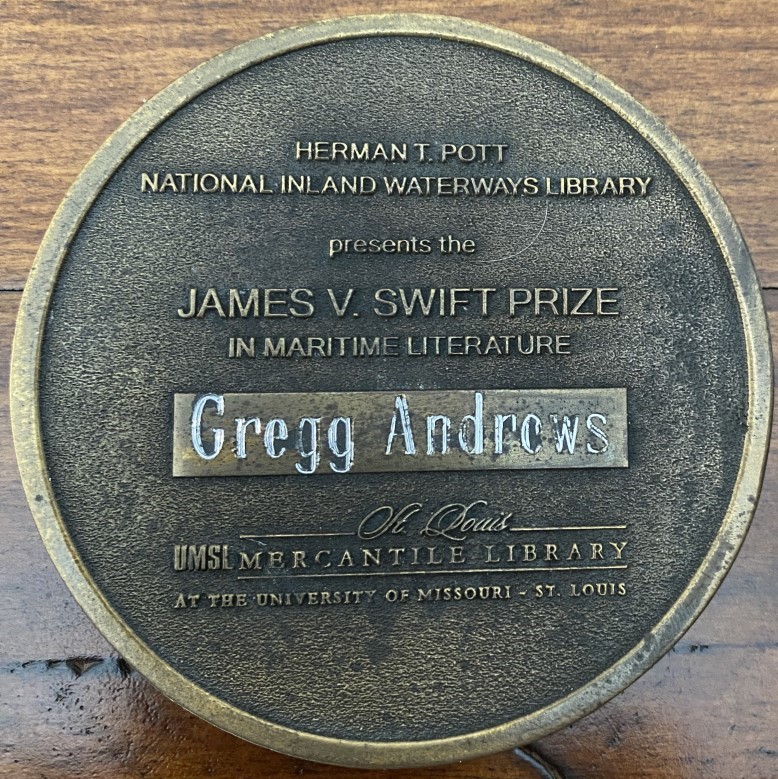

Gregg Andrews wins the 2023 Missouri Book Award!

The Place of the Two American Revolutions: A Fourth of July Celebration

A Renegade South reblog from 2020

By Vikki Bynum

This past week, in celebration of the 4th of July, I joined several historians to discuss the importance of the American Revolution and the American Civil War to the political transformation of our nation. In 1776, America moved from being a slaveholding colony to creating a nation, via the Declaration of Independence, founded on the principle of human equality. Only after decades of struggle and a protracted civil war did that principle became law. In 1865, the United States’ defeat of the Confederate States of America, which was formed to protect and expand the institution of slavery, opened the door to reconstructing our nation by amending its Constitution—first, by abolishing slavery, then, between 1868 and 1870, by bestowing rights of citizenship on freed people. For this reason, the Civil War is often called America’s second revolution.

This past week, in celebration of the 4th of July, I joined several historians to discuss the importance of the American Revolution and the American Civil War to the political transformation of our nation. In 1776, America moved from being a slaveholding colony to creating a nation, via the Declaration of Independence, founded on the principle of human equality. Only after decades of struggle and a protracted civil war did that principle became law. In 1865, the United States’ defeat of the Confederate States of America, which was formed to protect and expand the institution of slavery, opened the door to reconstructing our nation by amending its Constitution—first, by abolishing slavery, then, between 1868 and 1870, by bestowing rights of citizenship on freed people. For this reason, the Civil War is often called America’s second revolution.

But the hopeful beginnings of Reconstruction were followed by a tragic…

View original post 111 more words

Southern Civil War Union Soldiers on Memorial Day

For Memorial Day I’m reposting this in honor of Southern Unionists of Mississippi and Texas.

I received these photos from Deena Collins Aucoin this Memorial Day morning. The first is of Chalmette National Cemetery in New Orleans. The second is the grave of Riley J. Collins from Jones County, MS. An avowed Unionist, Riley resisted service in the Confederate Army, and joined Co. E, 1st New Orleans infantry (although his gravestone says LA Infantry) on April 30, 1864. He died of disease the following August.

Deena is a descendant of Simeon Collins, brother of Riley. Both men, along with brother Jasper Collins and many nephews and cousins, were members of the Knight Band in the Free State of Jones. Three other Collins brothers–Warren, Stacy and Newton–deserted the Confederate Army and fought against it in the Big Thicket of East Texas.

Vikki Bynum, moderator

The Free State of Jones on the podcast, “2 Complicated 4 History”

Below you’ll find my interview with Isaac S Loftus and Dr. Lynn Price Robbins, interviewers for the new podcast, “2 Complicated 4 History,” about the story and movie “The Free State of Jones.” A lively recap of the interview by podcast producers Jordan Sloane and Patrick Long, as well as Dr. Robbins, discusses historical accuracy versus Big Screen entertainment in the retelling of true stories.-–VB

Eliza Lucas Pinckney, 18th Century Entrepreneur – Dr. Lorri Glover – 2 Complicated 4 History

- Eliza Lucas Pinckney, 18th Century Entrepreneur – Dr. Lorri Glover

- The First Asians in the Americas – Dr. Diego Javier Luis

- The Osage Nation and Killers of the Flower Moon – Jim Gray

- Feed Drop – The Gilded Age and Progressive Era Podcast

- The Progressive Era and Modernizing the Presidency – Dr. Michael Patrick Cullinane

Gregg Andrews: “What the Mississippi River Means to Me”

At an awards ceremony inside the beautiful historic St. Louis Mercantile Library on April 6, 2023, I was honored to join the list of distinguished recipients of the James V. Swift Medal for excellence in maritime literature. Sara Hodge, Curator of the Herman T. Pott National Inland Waterways Library, presented me with the Medal for my book, Shantyboats and Roustabouts.

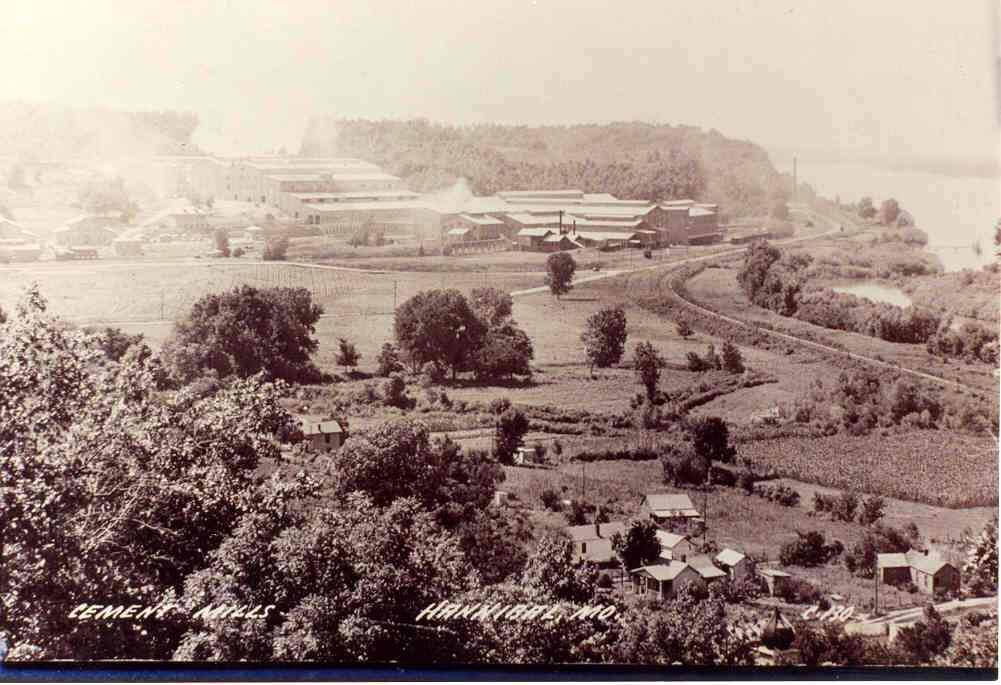

In a talk after the presentation of the Medal, I looked back on my riverbank childhood and the ancestral river heritage that inspired me to write the book. The Mississippi River has been a lifelong friend to me and a dynamic cultural influence on my writings as a historian and as a singer-songwriter. I grew up in Monkey Run, Missouri, a village of about 100 people in the river bottoms three miles south of Hannibal. Located in the northeast corner of Ralls County near the Mark Twain Cave, the village consisted of modest homes along the river and railroad tracks. Some might call them shacks, but we didn’t. Monkey Run once was a section of Ilasco, a cement company town of southern and eastern European immigrants torn down long ago. Monkey Run was inhabited mainly by fishermen and others like my father who worked at the cement plant, and my mother, a shoe factory worker and a retail clerk.

The river was my playground as a child. It was home. A place to fish, swim, and daydream on a pile of tangled driftwood where Marble Creek empties into the Mississippi. It was a place to while away the time and a place of many secrets. A place to sneak a cigarette, sip hurriedly from a nearly empty bottle of Old Crow whiskey hidden in the rafters of a neighbor’s shed. A place to build a raft, to ice skate, and a place for a treehouse in the tall cotton woods that blow little white kisses to float, flutter, and seed in the springtime air. Above all, it was a place to shake the blues. Sounds of barge traffic, freight trains, tugboats, calliopes, gandy dancers, and dance bands on excursion boats filled my childhood. For families like mine who lacked indoor plumbing, the river was sometimes a place to take a towel and a bar of soap before supper.

Until I left for college, I helped to set out trot lines, jug lines, baskets, and bank lines, and I camped, coon hunted, and duck hunted on the islands with kinfolks, friends, and commercial fishermen in the village. How well I remember tubs filled with beautiful buffalo, carp, perch, channel cat, and flatheads hauled up out of the river. I developed a love of the Mississippi but also a healthy respect for it. My earliest fragmented memory is that of a two-and-a-half-year-old toddler being rushed in my frantic mother’s arms down a dirt alley to the tracks and up the crossties to the mouth of the river, where a neighbor drowned. For all my mother knew, the victim might have been my father, who was fishing nearby when Walter “Tudie” Smith drowned in March 1953.

Three generations of my maternal grandmother’s family of day laborers, fishermen, and washerwomen were part of the waterways culture of shantyboats that flourished in the era of Mark Twain. In 1901, they were among those kicked off the southside levee at the foot of Jefferson Street in Hannibal. Burlington Northern Railroad agents and local vigilantes stormed in with steel bars and axes to drive them off the levee. They smashed the houseboats of owners who refused to leave as well as the boats that were unseaworthy. The attackers jeered and taunted waterfront dwellers and scattered the meager possessions of those who put up a fight on the shoreline. The sneering hatred directed at waterfront dwellers was palpable.

I left the Mississippi as an adult, but it never left me. The river followed me to Kent Finlay’s Cheatham Street Warehouse, a creaky little honky tonk in San Marcos, Texas, where my songs about the Mississippi River made me somewhat of an anomaly among Texas songwriters. In early 2020 when Covid imposed isolation and shut down the music venues, I decided at last to delve deeper into the world of my shantyboat ancestors on the waterways. It was something I had wanted to do for a long time. I had written many songs with a swampy blues feel to tell lost river stories, but now with my songwriter’s hat on a shelf indefinitely due to Covid, I put on my historian’s hat again and went to work. As the focal point of my new research project, the St. Louis levee offered a panoramic window into the world of the river poor in the Mississippi Valley at a time when the city transformed from a steamboat town into an industrial city. So, what began as an attempt to better understand my family’s river heritage became a book that contributes to our understanding of the cultural history of the Mississippi River.

What was it like to live a migratory life on the Mississippi? I believe Shantyboats and Roustabouts will help to provide answers, but I especially appreciate the way Clarence Jones answered the question in 1900. A young St. Louis trader who took up life on a Mississippi River houseboat after his sweetheart jilted him, he offered this observation to John Lathrop Mathews, a Chicago reporter and waterways writer: “I have been on the river three years. The first year you don’t like it very well, but you think it’s easy. The second year you have your doubts about how much the river could do to you if it tried. The third year you’re in love with it but you ain’t got no doubt you’re afraid of the river every minute, sleepin’ or wakin’.”

The Story Behind “Jones County Jubilee” and the “Free State of Jones”

Here’s how a lost story from the Leaf River swamp in southeast Mississippi turned into my song, “Jones County Jubilee.” The song’s roots are in a trip to Jones County, Mississippi in summer 1993 with my wife, Victoria E. Bynum, author of Free State of Jones. This was our second summer trip to Jones County. At that time, she was in the early stages of research for her 2001 book that led to a major Hollywood movie in 2016 starring Matt McConaughey. Without her book and our research trips, I never would have written the song. On that second trip, I was driving our little 1989 Mercury Tracer, searching for the old Mason Creek homestead site of Albert and Mason Knight, Newton Knight’s parents, when I spotted a guy in his truck out in a field. I pulled over and suggested that Vikki get out of the car and…

View original post 1,322 more words

Marvin Tupper Jones on the History of the Chowanokes of North Carolina

Renegade South is pleased to announce that Marvin Tupper Jones will lecture on North Carolina’s Chowanoke History on Tuesday, October 4, 11:30 am, at the Roanoke Chowan Community College in Ahoskie NC! “Last month’s talk in Elizabeth City,” he writes, “caught a lot of attention and even garnered a magazine article.“ (To review the earlier presentation, click here.)

Mr. Jones’s new lecture will include many new images and may also be viewed online. Whether you attend in person or virtually, please don’t miss it! —VB