Thanks to David Walsh and Joanne Laurier for permission to post on Renegade South their two-part interview with me for the World Socialist Web Site. –VB

“The records were full of evidence of dissent and insurrections by common people”

By David Walsh and Joanne Laurier

12 July 2016

PART ONE | PART TWO

Introduction by David Walsh

Free State of Jones, the film directed by Gary Ross, powerfully and movingly recounts a significant episode of the American Civil War, the insurrection against the Confederacy led by Newton Knight, a white, antislavery farmer in Jones County in southern Mississippi from 1863 to 1865.

Audiences have been generally warm and receptive. However, Ross’s film has met with a hostile response from commentators who see society and history in exclusively racial terms, like Charles Blow of the New York Times (whose own lead film reviewer, A. O. Scott, to his credit, gave the film positive marks), Vann Newkirk II in the Atlantic and countless others. Free State of Jones is a blow to the practitioners of identity politics because it presents this revealing episode in American history in terms of class conflict.

Moreover, the fraternity of well-paid, thoroughly self-satisfied film critics, white and black alike, quite rightly perceive in Free State of Jones a social and political threat: that the interracial revolt against inequality and aristocratic privilege in the 1860s will find an echo in our day.

Free State of Jones has absurdly been characterized as advancing some sort of “white savior” mythology because it honestly presents the response of common people in Mississippi, inspired by the traditions of the American Revolution, to the reactionary project of Southern secession. This cuts across the effort in particular to paint the white population in America, past and present, as hopelessly backward and racist.

Whatever the immediate commercial fate of Ross’s film, it will have a long shelf life. Those who are serious about American history and contemporary social life will find in it both education and inspiration.

Victoria Bynum

Victoria BynumOne of the works that influenced Ross to make his film was The Free State of Jones: Mississippi’s Longest Civil War (2001), by Victoria Bynum. The book provides a fascinating, well-researched account of the Knight Company, tracing the origins of the ideological outlook of the antislavery, Southern Unionist forces back to the American Revolution, and beyond.

As the American Historical Review noted, “Bynum has fashioned frustratingly disparate material into an important book that may cause historians who are skeptical about putting too much stress on an ‘inner’ Civil War to rethink their position.” The same journal commented, “Prodigious research in genealogical material, census files, church records, official documents, and oral histories provides as full a picture of Jones County and its people as we are ever likely to have.”

Victoria Bynum is Distinguished Professor Emeritus of History at Texas State University, San Marcos. A graduate of the University of California, San Diego, an award-winning author and National Endowment for the Humanities Fellow, her scholarship analyzes class, race and gender relations in the Civil War Era South. Her blog, Renegade South, features unruly women, mixed-race families, anti-Confederate guerrillas and political dissenters.

She is the author of the following books:

The Long Shadow of the Civil War: Southern Dissent and Its Legacies. University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

The Free State of Jones: Mississippi’s Longest Civil War. University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

Unruly Women: The Politics of Social and Sexual Control in the Old South. University of North Carolina Press, 1992.

We spoke to Victoria Bynum recently about Southern Unionism, Free State of Jones and the historical and political questions raised by her research and interests. It was a lengthy and absorbing conversation. As a personal aside, we will also let the reader know that she was a joy to talk to!

* * * * *

David Walsh: First, can you tell us something about your background and how you made your way to the study in particular of Southern Unionism and opposition to the Confederacy?

Victoria Bynum: I don’t come from an academic background. Neither of my parents graduated from high school. My dad was born in Jones County, Mississippi, but he left the state at age 17 to join the military. That’s how he made his living; he was a master sergeant by the time he retired. In my family, work was valued over education.

I grew up in the fifties and sixties, during the era of the Civil Rights movement. Influenced by my mother, who supported racial equality, I was very affected by this period. Over time, I developed a strong desire to go to college, and at age 26 began taking classes at a community college. To cut to the chase, my early interest in the history of race and social class emerged from my own experiences. When I began college I was a divorced mother on welfare. Pursuing a doctorate in history required a long economic struggle, one that ended after I finally obtained my degree and began teaching at Texas State University.

I began my college research with an interest in “free people of color,” the designation applied to free people before the Civil War. I was initially intrigued by a black friend’s insistence that his Virginia ancestors had never been slaves. That seemed to me unusual, and it piqued my interest in Old South history. Along the way, I became interested in both free black women and white women who lived outside the planter class. Those interests resulted in my dissertation (and first book), Unruly Women: The Politics of Social and Sexual Control in the Old South.

While working on my dissertation, “Unruly Women,” I expanded my research into the Civil War, and that’s where I discovered Southern Unionism. The records were full of evidence of dissent and insurrections by common people, and it fascinated me. Here were white non-slaveholding men, women who allied with them, free people of color and slaves—all engaged in acts of subversion against the Confederacy. I had never known that actions like these occurred on the Civil War home front.

I was only studying North Carolina at the time. But, in the back of my mind, I remembered the story of Jones County, Mississippi, because my father was from there. I remembered reading years earlier in a footnote the legend of how the county supposedly seceded from the Confederacy. I didn’t really know what it meant for a county to “secede” from the Confederacy, but it got my attention. So after I completed Unruly Women, which included two chapters on Southern Unionism, I decided to make my second book about the county in which my father was born.

It was a hard history to write because there were not nearly the court records documenting the Jones County insurrection as I’d found for Civil War North Carolina. The North Carolina governors’ papers, court and legislative papers, are filled with information on insurrections and inner civil wars for several parts of the state, not just one. The Mississippi archives offered less evidence, but, in many ways, offered the most interesting guerrilla leader of all, Newton Knight.

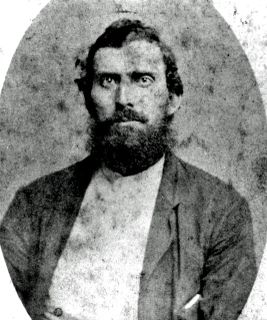

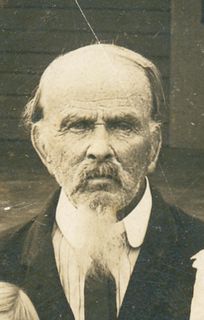

Newton Knight

Newton KnightIn writing The Free State of Jones, I decided to draw a broader picture of the region’s insurrection by tracing the historical roots of its peoples’ ideas about authority, power and legitimate government. That’s why the book begins with the American Revolution––and even before. After finishing that book, I expanded my research on Southern Unionism into Texas.

So I’ve now published works that trace both the roots of Southern Unionism and the eruption of Civil War guerrilla warfare in three different states. As the stories of Unionism became ever more interesting, it also became evident to me that they are an important and largely unknown part of American history. Even though there have been numerous studies by various historians—I’m not the only one by any stretch—the stories never seem to move far beyond academia and into the popular mainstream and consciousness. That’s what I find so exciting about Free State of Jones, the movie.

DW: I would like to know your opinion about the responsibility and job of the historian. We have lived through 30 to 40 years in which the very ability of human beings to determine the truth about the past has been seriously called into question, by postmodernism and other trends. And yet there remain historians like yourself and others who are very committed to historical truth. Our own view is that postmodernism and identity politics are closely related. The conception that there is no such thing as objective truth, that everyone merely has his or her “narrative” has had pernicious consequences. But I will ask your view on the matter.

VB: My attraction to historical research began before I entered college, and I have always shied away from adhering to any particular theoretical approach that might dictate my response to evidence. Of course, I have been influenced by any number of theories, and those influences show throughout my books. Obviously, Marxist theory influences my analysis of class, whereas postmodernism influences my deconstructionist approach to racial identity. A good deal of feminist theory—which is anything but monolithic—informs much of my discussion of the place of gender in conflicts that appear on the surface to be centered exclusively on males.

While my overarching thesis statements reflect theoretical influences, my commitment is to historical truth as I perceive it through my own careful analysis of evidence. Within this process, I have little patience for “identity politics.” As much as I hate the phrase “political correctness” when applied to liberals and leftists by racists and right-wing extremists, I have come to recognize identity politics—as recently demonstrated by Charles Blow of the New York Times—as another pernicious form of political correctness that uses hot-button phrases connected to discrete historical victims (in this case, slaves) to shut down any discourse that threatens that particular victim with a shared stage (say, poor whites).

For example, Blow’s expressed indignation in a New York Times op-ed over contents in both the movie, Free State of Jones, and my own book not only denies the importance of class to relations between non-slaveholders and slaves, it is thoroughly male-centered, leaving enslaved women with no agency whatsoever in regard to their sexual choices. It is fine to label as potentially “rape” all sexual advances made by slavemasters toward slaves; clearly, slaves had no ability to say “no” to such advances. It is not accurate, however, to label all sexual activity between white men and enslaved women as rape, as Blow also does. His rhetorical point does violence to history.

Joanne Laurier: Gary Ross’s film has come under what we consider to be politically motivated attacks. What is your opinion of the film?

VB: I’ve read every review of Free State of Jones I could get hold of and have thought carefully about the film myself. My husband and I previewed it on June 2 and we liked it very much. (So, I might add, have the people who have since seen the movie and expressed their opinions to us directly.)

Free State of Jones

Free State of JonesFrankly, I was relieved by what I didn’t see in the movie as well as what I saw. There were so many things that Gary Ross could have done with that story—things one might expect a Hollywood director or screenwriter to do—that he didn’t do. He did not, for example, graphically exploit the relationship between Newt and Rachel. He understated it if anything, which caused a number of reviewers to complain that the relationship did not come to life for them. One can only imagine, however, what other reviewers would have said—particularly Charles Blow—if Gary Ross had enlivened the screen with hot sex scenes based on mutual lust.

And then there are charges by critics that this is just another “white savior” movie. Such charges reflect a lack of knowledge about the role of class in stimulating white disaffection with the Confederacy. To such critics, I would ask: how should one portray these events and remain true to history? This is the true story of a man who actually collaborated with slaves during the Civil War to defeat the Confederacy. During Reconstruction, he worked to achieve rights of citizenship for freed people.

Are we to pretend that blacks could have achieved such rights without white assistance in the post-Civil War period, a period in which black people were murdered by whites with impunity, not just by the Ku Klux Klan, but by whites who didn’t even bother to put the hoods on? If we’re going to make historically based movies, we must present the past with factual realism or the endeavor will be worthless.

Likewise, when I hear some critics argue that Newt Knight should not have been the central character in a movie that includes slaves, I remind them that his remarkable story has never been told to a mass audience. Are we forbidden to tell the story of an ordinary white man who acted in extraordinary ways, simply because too many movies have not presented the history of blacks accurately? We need movies that tell the history of both blacks and whites accurately. Let’s tell the story of Newt Knight as well as those of Nat Turner and Harriet Tubman, remembering that together, these stories reveal the intersection of class, race and gender in history. Of course there have been “white savior” movies, just as there have been a host of movies that exploit the brutality of slavery by including as much gratuitous sex and violence as possible.

Free State of Jones

Free State of JonesBut Ross’s movie is not one of those exploitative films. And that is what I find perplexing about many reviews of it. It’s as though some critics haven’t paid close attention to the fact that—as several counter-reviewers have pointed out—Newt Knight doesn’t save anybody. He can’t save Moses. He can’t relieve the hopelessness that Rachel expresses when she begs him to consider their moving north. The counterrevolution against Reconstruction is still with us today. Where’s the “white savior”?

That’s why, as you pointed out in your own review of the movie, Joanne, that we still abide by a counter-version of the Civil War that is based on lies: the lie that the Civil War was not caused by slavery, the lie that slavery was a benign institution. The other big lie of this “Lost Cause” version is that Southern whites were all solidly behind the Confederacy.

And so, when I read a review that dismisses the movie as just a “white savior” fantasy, it’s as though the reviewer is saying, “Oh, no, we don’t want to hear that the white South wasn’t solid. We know all those white guys were united, fighting to save slavery, raping black women and putting hoods on their heads after the war. That’s the only South we know, or ever will know.” In the end, such critics echo the reactionary white supremacist version of history that prevailed by the early twentieth century. They, too, claimed that the white South was “solid.” And well they could, for they had won their counterrevolution against Reconstruction.

Despite being dismayed by many of the reviews, I must say that academic historians—many of whom I’ve never met; others who I know personally—love this movie. It’s not that they think it’s perfect; they love it because for the first time we’re seeing a Hollywood film that takes on the “Lost Cause” myth and accurately presents the long-neglected history of Reconstruction.

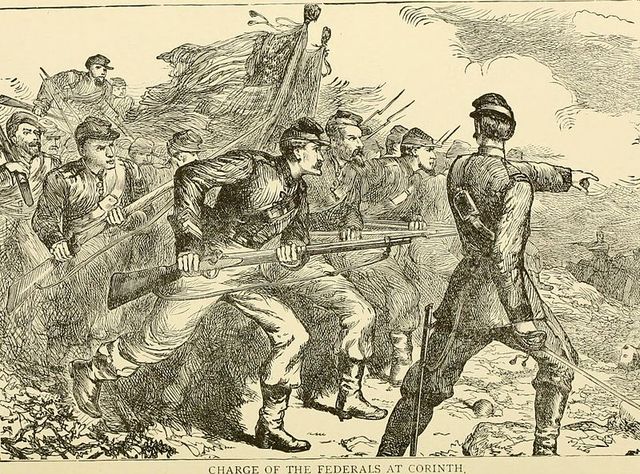

Charge of the Federals during siege of Corinth, Mississippi, April-May 1862

Charge of the Federals during siege of Corinth, Mississippi, April-May 1862DW: You’ve already referred to it. You responded strongly to Charles Blow’s comment in the New York Times. Could you perhaps go over your objections to his op-ed column and, more generally, your attitude toward racialist politics?

VB: The manner in which Blow attacked my work was dishonest. Specifically, he presented a certain passage from my book that, if read outside its context, appeared to be a deliberate effort on my part to avoid using the word “rape.” In fact, I was referring to actual laws passed within Southern states that forbade interracial contact between whites and blacks. Those laws existed precisely because such contact was common. They were passed piecemeal from the colonial years forward to forbid just the sort of cross-race alliance that occurred between Newt and Rachel Knight during the war.

Blow’s comments reveal his ignorance of this history. During the past several decades, historians have uncovered a wealth of evidence about sexual and nonsexual consensual relationships between the races in the colonial and 19th century South. As dehumanizing and brutal as slavery was, the institution was not a giant concentration camp. Resistance to slavery was far more subtle than studying slave revolts will ever reveal.

Some 75 percent of whites did not own slaves; small populations of free people of color lived in the slaveholding states. Slaves interacted regularly with these groups. Though interracial contact was frequently exploitative, it also contributed to everyday resistance to the totality of slavery. Rachel Knight may well have initiated her relationship with Newt Knight, and it appears likely to have been in her interest to do so. Only she can say for certain.

Part II

“Ordinary people truly imbibed the principles of the American Revolution”

An interview with Victoria Bynum, historian and author of The Free State of Jones—Part 2

By David Walsh and Joanne Laurier

13 July 2016

PART ONE | PART TWO

This is the second part of a conversation with Victoria Bynum, the author of The Free State of Jones: Mississippi’s Longest Civil War (2001), a work that inspired the recent Gary Ross film.

The book and film tell the story of the insurrection against the Confederacy led by Newton Knight, a white, antislavery farmer in Jones County in southern Mississippi from 1863 to 1865.

* * * * *

David Walsh: This is a two-part question. Your book, The Free State of Jones, does not begin in 1863, but discusses the processes that made the Knight Company possible, tracing them back in particular to events that took place in the Carolinas before the American Revolution. Could you speak a bit about the influence of the Regulator Movement [a protest movement in the Carolinas in the 1760s against corrupt government], and perhaps explain what it was?

Related to that, you write: “But before the nineteenth century—and especially before slavery became firmly entrenched in the Carolina and Georgia back-countries—racial identity was more fluid, even negotiable in some cases.” And later, “the bifurcation of racial identity into discrete categories of black and white was a long and ultimately illusory process.”

Victoria Bynum: That statement points to the intersection of race and class among the colonial underclass before the dramatic rise and consolidation of slavery following the American Revolution. When I first began my doctoral research for “Unruly Women” in North Carolina records, I was struck by the number of interracial marriages that went unnoticed, and even unnoted insofar as race, in colonial records.

More and more, later on, racial differences were noted in court records of property and marriage, while laws specifically forbidding the mobility of free people of color and interaction between whites and people of color (even in “bawdy houses”) were proscribed by law during the 1820s and especially the 1830s. We are seeing during those years the rigid institutionalization of both slavery and identification of one’s civil rights, or lack thereof, along lines of race. And yet, race-mixing continued, requiring that white people with any known African ancestry be defined as “black” in order to protect the fiction that slavery was based exclusively on race.

The Regulator Movement, which occurred in the 1760s, was an uprising of white men of property who felt their economic independence slipping away. They especially resented corrupt “courthouse rings” of lawyers, planters and merchants, representative of North Carolina’s emergent economic elite.

This was an early stage of capitalistic development that threatened propertied farmers and led to an uprising against the corruption associated with county government. What was so interesting to me, as I did my research, was just how many of the Jones County fighters against the Confederacy turned out to be descendants of North Carolina’s Regulators.

A direct link between the neighboring South Carolina Regulator Movement and “fluid” racial identity appears in the person of a light-skinned, mixed-race individual named Gideon Gibson. Gibson was both a slaveholder and a Regulator. Because of his Regulator activities, he was accorded a level of respect usually reserved in white society for white men. As racial lines hardened, many descendants of families like the Gibsons were forced to move west in order to remain “white.”

There appears always to have been a small class of free people of color in the American colonies. At first, most laborers were white indentured servants. But by 1680, Africans were being brought over mostly as slaves. There’s a period of about 60 years during which black slavery replaced (mostly white) indentured servitude.

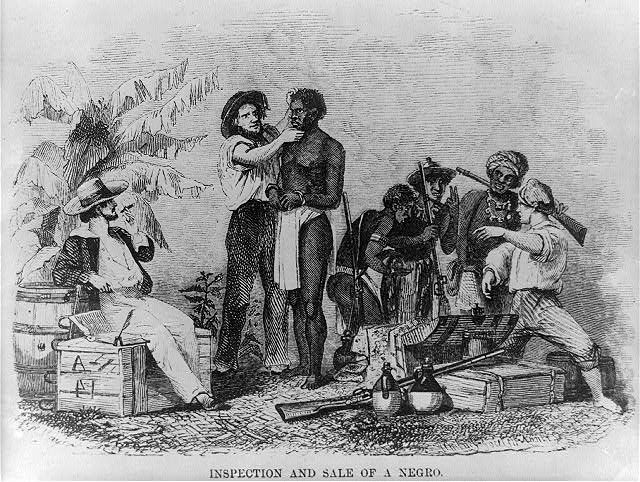

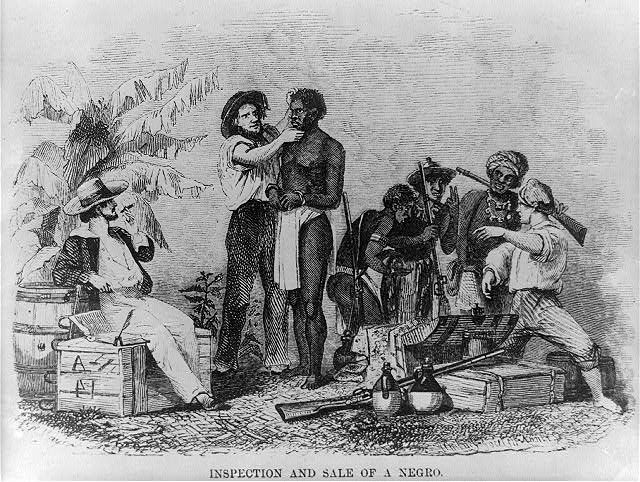

“The Inspection and Sale of a Slave”

“The Inspection and Sale of a Slave”By 1680, it had become more profitable to purchase slaves than to bring over indentured servants. Life spans were increasing by mid-century, so if you bought a slave, he or she was likelier to live a full life, and you were likely to get a return on your investment. In an earlier period, indentured servants were lucky if they lived through the terms of their indenturement. Why bother then to buy a slave? You just brought over an indentured servant, white or black, he or she died, you collected his or her “freedom dues” [the payment an indentured servant received at the end of his or her term]. Then you brought over more servants. This brutal system of labor led, of course, to the more brutal system of chattel slavery.

Joanne Laurier: Can you speak about the influence of the American Revolution and the War of 1812 on the Jones County insurrectionists?

Victoria Bynum: On the basis of extensive research, I came to the conclusion that the American Revolution and the War of 1812 were important “nationalizing” events that truly impacted the consciousness and ideological orientation of many of the ancestors of the Jones County Unionists.

Some of the most critical bodies of records in this regard are the territorial records of 1812-1815 for Mississippi and Alabama. The surnames of core members of the Knight band kept coming up, as did the names of some of the most prominent supporters of the Confederacy as well.

“Declaration of Independence,” John Trumbull (commissioned 1817)

“Declaration of Independence,” John Trumbull (commissioned 1817)As Jones County’s ancestors migrated across the southwestern frontier, their names appear over and over on frontier petitions sent back east to the federal government. In proclaiming their need for federal assistance, many of these petitions quoted directly from the Declaration of Independence in citing the principles of representative government in their demands.

The petitions’ signers called on the federal government to abide by its contract with the people. And they were the people. They wanted counties created, they wanted judges sent out so that they could have an adequate court system, they wanted troops sent to help them fight Indians. As Jeffersonian farmers, they believed they had superior claims to the land. At the same time, some petitions describe US soldiers as being worse than the Indians. Such complaints presage later complaints about the Confederacy, with frequent charges that US soldiers were pillaging their settlements.

In these petitions are clear indications that early frontier common people developed anti-authoritarian attitudes, or perhaps more accurately, a mistrust of authority, based on their experiences moving west. For their part, government authorities frequently referred to the common folk of the frontier with undisguised contempt.

Reading these records, it struck me that ordinary people truly imbibed the principles of the American Revolution. These were not just frontier followers or “rabble”—many of their families would became important figures in Jones County long before the Civil War. They believed in a nation in which their lives would (or should) be made better by reproducing “civilization” through county governments on the frontier. They were imbued with Jeffersonian agrarian ideals that insisted on the “virtues” of small producers; they saw themselves as expanding the nation as well as their own prosperity.

Fifty years later, it would not be a great leap for the children of these veterans of the American Revolution and the War of 1812 to view the Confederacy as a corrupt, illegitimate government, one that threatened to destroy the nation through secession.

Despite excellent academic studies of the Southern yeomanry, popular culture often conflates small landowners who owned no slaves with impoverished “poor white trash.” In the 19th century, white poverty was dismissed as the result of defective genes, the class structure of Southern society largely ignored. This is still true today. And yet, as historians have tirelessly pointed out, propertied yeoman farmers vastly outnumbered both slaveholders and propertyless poor whites.

JL: You explode the myth of Knight as a mere “hyper-secessionist” and demonstrate that he was a pro-Union fighter. He also seems to have been genuinely color-blind, in spite of the super-charged times.

VB: Newt Knight was very unusual in his social behavior; he openly lived among his mixed-race family members for the rest of his life.

In relation to the myth of Knight Band members being “hyper-secessionists” rather than Unionists, I found much the same stereotype presented in literature surrounding Warren J. Collins, the brother of Jasper Collins, who led a similar revolt in Texas against the Confederacy.

Such literature condescendingly presents Unionists as mere “good old boys” who were so rebellious that they could not even obey the authority of those leaders to whom they should have deferred. As a result, Southern Unionists are reduced to little more than poor white boys “on a tear.” It fulfills the old stereotype that Southern white boys just like to fight, that they’re “touchy” about authority. You can’t say anything to them, they’re always ready to put their fists up, or pull out a gun.

In my work, I have tried to expose the good-old-boy trope for what it is—an effort to paint backcountry Southern Unionists as non-ideological simple folk who didn’t want to fight for either side, and just wanted to be left alone. There’s a certain amount of truth to that: they did want to left alone, but it wasn’t true that they didn’t support either side. They took a clear stand for the federal government and the Union.

Scene from Free State of Jones

Scene from Free State of JonesThe Free State of Jones represents one of many popular movements against the Confederacy that occurred throughout the South. Take the role of women, for example. There were so many more ways that women resisted Confederate forces than by picking up guns. I love the scene in the movie, Free State of Jones, where Newt teaches three little girls how to shoot a gun. But women also poisoned bloodhounds with red pepper and broken glass. They were more likely to pick up a fence rail and knock a Confederate soldier over the head than to have a gun handy. They met deserter hunters at their own front doors to convince them their hidden men were nowhere around. The history of these inner civil wars is full of rich details.

DW: You write in The Free State of Jones that the Collins family, so prominent in the Jones County events, “personally disapproved of slavery but did not believe that the federal government could constitutionally force its end. By the same token, they did not believe that the election of Abraham Lincoln provided constitutional grounds for secession.”

As far as can be determined, what were the social views of the most radical members of the Knight group? Toward slavery, toward abolition, toward equality of the races?

VB: That’s a very good question. Here’s the problem. Jones County elected a “cooperationist” delegate, John H. Powell, to the Mississippi state convention in January 1861. As a cooperationist, Powell was against seceding from the Union simply because Abraham Lincoln had been elected. The cooperationists wanted to “cooperate” further with the North, perhaps effect a new compromise over slavery.

The pro-secessionist forces, however, believed that Lincoln was no better than the abolitionists, that he was a secret abolitionist linked to John Brown. They wanted to secede and, obviously, they won the day in Mississippi and throughout most of the South.

But we really don’t know for certain what the men who voted for Powell thought. If Jasper Collins believed that the US Constitution did not allow the federal government under Lincoln unilaterally to abolish slavery, he was in line with Lincoln, who did not believe that Congress had the constitutional right to abolish slavery either. Lincoln was no abolitionist then, but he did believe that Congress could limit the expansion of slavery into the territories. Containment of slavery was Lincoln’s answer.

Pro-secession slaveholders knew as well as Lincoln did that containment of slavery spelled doom for the institution. The North would gain greater power in Congress with western free states. Eventually, slaveholders would have nowhere to go with an expanding population of slaves, nor would they have access to fresh lands. It’s certainly possible that Jones County’s Unionists knew this, too—and welcomed it as an end to slavery.

I think it’s safe to say that core Unionists in Jones County disliked—maybe even hated—slavery. Though I’ve seen no evidence they were abolitionists, the fact that they did not own slaves supports their decision to oppose secession and to fight against the Confederacy.

Incidentally, in 1892, Newt Knight made an interesting statement during a casual interview with a reporter. Asked about his Civil War exploits, in hindsight Newt expressed the wish that the nonslaveholders had risen up and killed the slaveholders rather than being “tricked” into fighting their war for them.

DW: Did the Unionists in Jones County not own slaves simply for economic reasons, or were there also ideological, political sentiments involved?

VB: That is the big question, one that I’ve never quit asking. I always turn to the Collins family for evidence because its members so consistently resisted owning slaves, and because they all supported the Union. It appears that their resentment of slavery was based on a self-conscious identification of ideological class interests.

I certainly don’t see the Unionism of the core Knight Company members as a knee-jerk reaction to economic devastation. These individuals didn’t simply turn against the war and the Confederacy out of concern for their families; they opposed secession from the beginning.

JL: Your research has revealed the more or less direct, personal connection between the Knight Company and the Collins group in Texas and the birth of the Populist and Socialist parties in the region. Could you please speak about this?

VB: That connection was a fascinating and surprising aspect of my research. I learned from an independent researcher that Jasper Collins and his son founded the one and only Populist newspaper in Jones County, the Ellisville Patriot.

Jasper Collins

Jasper CollinsThrough newspaper research, I discovered that Jasper, his son and a nephew became delegates to the 1895 People’s Party [Populist] convention. I’ve never found a reference to Jasper Collins making the transition from the People’s Party to the Socialist Party, but several of his younger kinfolk did. In 1915, shortly after Jasper’s death, several of his relatives ran for local offices in Jones County on a Socialist ticket.

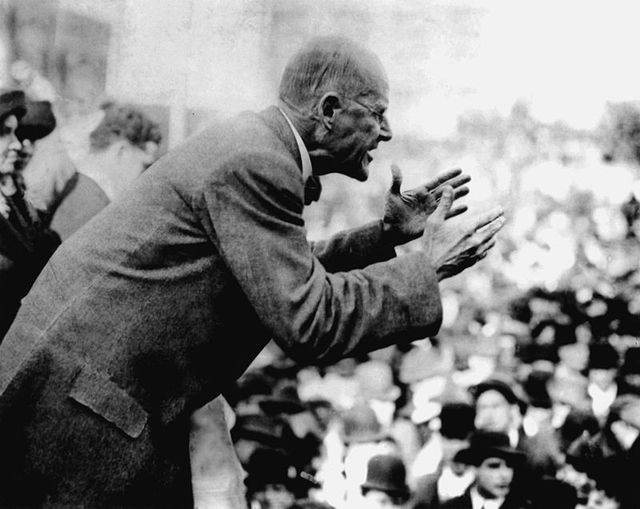

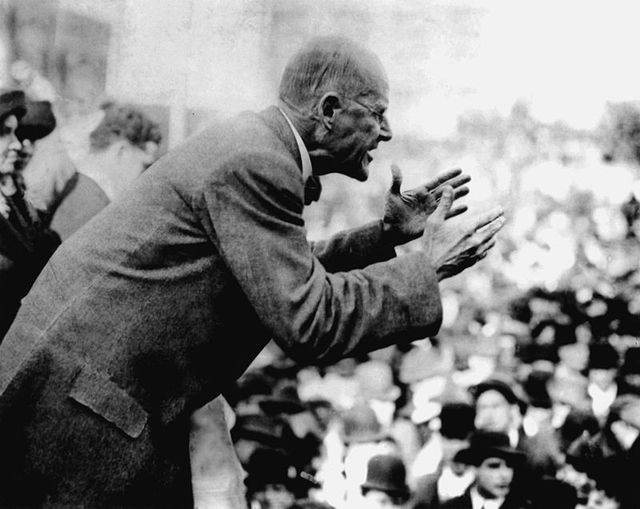

Now, move over to Texas, and you have Jasper Collins’s brother, Warren J. Collins, the Civil War Unionist who headed his own deserter band in the “Big Thicket” of East Texas. Warren ran as a Socialist for office in 1910 and 1912. He was an outgoing and outspoken socialist who enthusiastically supported Eugene V. Debs.

Socialist Eugene V. Debs

Socialist Eugene V. Debs in 1912

I suspect that Warren Collins traveled the same Populist route to Socialism in Texas as did his Jones County kinfolk in Mississippi. I’ve learned that some of my own Bynum relatives—those who were Unionists and who intermarried with the Collinses—also became Populists and Socialists.

I believe it’s probable that Newt Knight would also have joined the Populist and Socialist political movements after his participation in Radical Reconstruction if not for the notoriety of his interracial family. The defeat of Reconstruction and the victory of white supremacy derailed Newt’s chances of winning office and cut short his political career.

All in all, I’m grateful that Gary Ross and Hollywood appreciated the historical and political relevance of this story, for we’ve suffered the effects of “Lost Cause” history for far too long. Today more than ever we need history grounded in deep research and not in the political rhetoric of racialists from either the 19th or the 21st century.

Concluded

Newton Knight

Newton Knight Free State of Jones

Free State of Jones Free State of Jones

Free State of Jones Charge of the Federals during siege of Corinth, Mississippi, April-May 1862

Charge of the Federals during siege of Corinth, Mississippi, April-May 1862 “The Inspection and Sale of a Slave”

“The Inspection and Sale of a Slave” “Declaration of Independence,” John Trumbull (commissioned 1817)

“Declaration of Independence,” John Trumbull (commissioned 1817) Scene from Free State of Jones

Scene from Free State of Jones Jasper Collins

Jasper Collins Socialist Eugene V. Debs in 1912

Socialist Eugene V. Debs in 1912